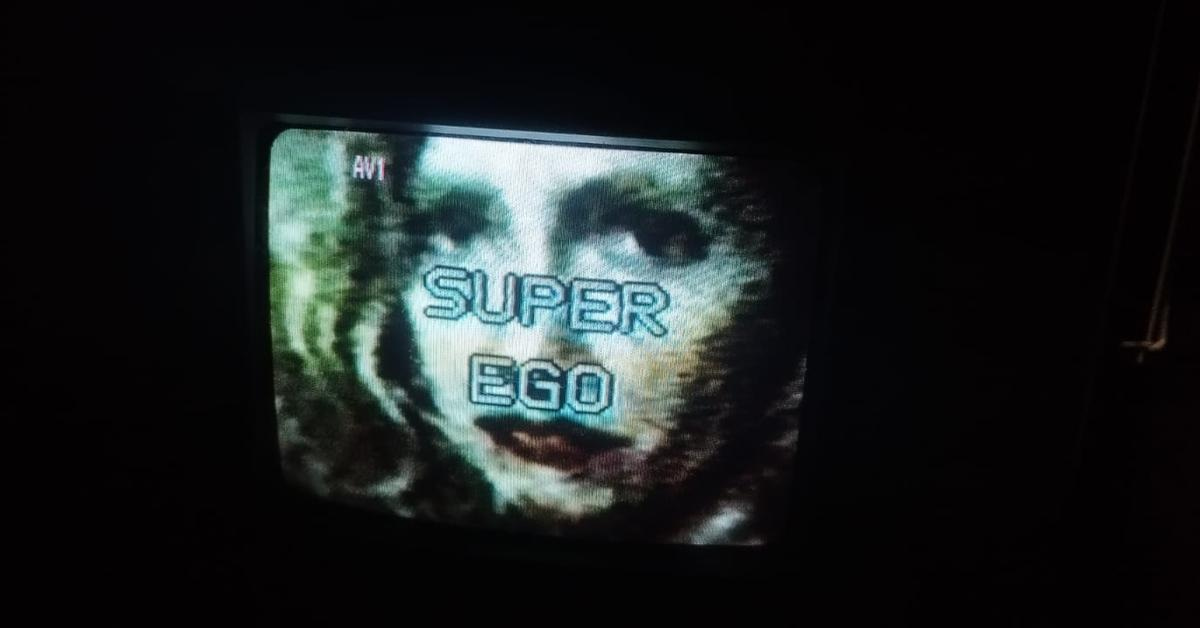

One of the tallest curators in London squeezes into a tiny office cubicle, its glass doors taped over with black rubbish bags to make a dark room. He trips over a little poet sitting cross-legged on the floor; he is followed closely by an average-build artist, like clowns piling into a car—part magician’s trick, part traffic jam. On a TV, the kind you might have found in a teenager’s bedroom in the early 2000s, Malga Kubiak’s Super Ego (1987) plays on a loop: a seventeen-minute video of a ritualistic bacchelorian dinner party in which a man and child are served up as sacrificial delicacies.

Malga Kubiak is a cult figure, born in Poland, she has been working in Sweden since the 1980s. In her films, writing, and live performance, Kubiak presents a raw and confrontational sexuality. Her body, shown as desiring and consuming, is the site and instrument of her practice. For this screening, Katie Shannon and Keira Fox―known collectively as TLC23―selected five video works made between the late 1980s and early 1990s: Ego (1985), Super Ego (1987), Father (1989), IDN 1 (1990), IDN 2 (1991). Screened as a matinee at the last instalment (for now) of Existers, Adam Gallagher and Ruth Angel Edwards’ self-organised, periodic exhibition and events programme on the sixth floor of the old Meta headquarters on Shaftesbury Avenue.

The installation made use of two breakout rooms and one main meeting space. Ego and Father were projected at opposite ends of a conference room, the conference table still in place. In Ego, Kubiak performs. In some scenes directly to camera—pulling down her red dress, baring her teeth, cocking her head, presenting her cunt and masturbating. In other segments, she’s on stage, and then in another sequence, she is shown having seemingly real and enjoyed sex with a partner. Father depicts the relationship between the female artist and a father-poet figure. “I feel like I’ve found someone’s parents’ home pornos,” says the tall curator. “I’m going to have to go.”

They say that men look at women, and women look at themselves being watched, this was John Berger’s formulation in Ways of Seeing (1972). In Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (1975), Laura Mulvey coined the theory of the “male gaze.” Drawing on informal translations of Lacan, she wove ideas of scopophilia, misrecognition, and lack into a framework that has since come to both define and often overdetermine feminist and female-centric visual culture. But these days, everyone’s a girl Narcissus—preening into and spying through their phones. Kubiak’s cold histrionics are a delight: cool, sexy, and just distant enough to become an object of curiosity. The work is positioned somewhere between Mulvey’s insurgent institutional critique and the algorithmic pleasures of today’s regime of enjoyment of the face.

In Ego, a non-diegetic soundtrack modulates Kubiak’s performances, a sonic container and mechanism that acts as an authority over egoistic expression. Like the superego that Kubiak works with more directly elsewhere, this structuring and limiting function emerges from the work's interior logic, which, of course, has no autonomy from the artist. Watching Kubiak watch herself, we are drawn into the recursive feedback system of feminine sexuality. Crouched beside the abandoned office furniture of Meta—the devalued remnants of an operation intended to interconnect virtual spaces for work, play, and socialising—we find ourselves within the architecture of the expropriated superego.

Existers came into being after Gallagher and Edwards were offered temporary occupation of the disused office block, managed by Bow Arts, before the central London building was sold for redevelopment. Exciting and influential artists in their own right, Gallagher and Edwards are committed to a form of DIY and self-organised culture recognisable in the punk materiality of Kubiak’s films. For eight months, starting in mid-2024, Existers has hosted events, exhibitions, and collectives. TLC23’s installation and screening closed out the first chapter of the series, though Existers will find new life at another venue.

Like Gallagher and Edwards, Shannon and Fox are nodes within a promiscuous eco-organism of artists, musicians, and designers. They organise club nights, screenings, and performances, in which, like Kubiak, their bodies are the central element of expression and communication. As a generation, they—and we, and I—have been sutured between the bloated positivity of the pre-2008 financial crash and the mercantile pragmatism of a generation born into the digitised world. The invitation to squat—whether as a pop-up, guardianship, or temporary art project—is a gesture that has formed and characterised much of this era’s cultural and economic productivity.

The term “sharing economy” was recently a fashionable way to describe peer-to-peer wealth and content generation; in Existers and TLC23, however, we encounter a different model, one of redistribution born from a near-total lack of resources. That said, Shannon & Fox sounds like an upmarket estate agent, so if they were to switch to an eponymous firm name, they could have a go at inverting the supply chain, which currently seems over-extended, saggy, and full of holes.

The bin bags taped over the glass windows of the break-out rooms just about did the trick. Provisionality, as both a generous and temporary gesture, defines the aesthetics of TLC23 and Existers. The shonky obsolescence of the installation’s TV screens and Kubiak’s video technology, bagged up inside office rooms, flickered and strobed. The performances’ choreographed hysteria seems to shudder against the screen. In the “wasted space” of the tech headquarters, Kubiak’s films are like a nail busting through the end of a high-heeled shoe, teetering on the edge between comedy and disaster. Crammed in together, crouching on the floor, the distinction between the bodies on screen, the hosting bodies, and the viewer begins to blur, as the feedback loop of representation and desire tightens into a pleasurable kind of pressure.